Poverty, illiteracy, hunger and nomadism as social, cultural and economic reasons of treatment abandonment in HIV/AIDS patients in Mozambique.

Leonardo Palombi,1 Nelson Moda2

1 University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

2 Zambeze University

Introduction

Despite huge investments and many non-governmental organizations reinforcing the government on the challenge of HIV-AIDS in Mozambique, HIV incidence and the number of individuals abandoning the treatment continue to rise. According to UNAIDS, in the east and south Africa regions HIV prevalence in people from 15 to 49 years was 7.0% (6.8%-7.7%). Mozambique’s HIV prevalence is 12.3% (10.6% - 18.9%), the eighth highest in the world (UNAIDS, 2017; UNICEF, 2017).

As of 2018, 2.2 million people live with HIV in Mozambique with 150,000 newly infected people per year.1 Women are disproportionately affected: about 60% of the adults living with HIV are women, and new infections among young women (ages 15-24) were almost double compared to young men. More than 95% of pregnant women living with HIV were able to access ART to prevent transmission to the new-borns, preventing therefore about 18,000 new HIV infections per year among infants. In terms of coverage of health facilities offering HIV treatment in Mozambique, based on a 2020 Minister of Health (MISAU) report, from 2003 to 2020 Mozambique reached a 95% coverage. This means that from 1,721 existing public health facilities, 1,633 offer HIV treatment at different levels (MISAU, 2020:47). However, lifelong antiretroviral treatment is often associated with high levels of interruption, abandonment, and loss to follow up (LTFU).2,3,4

This article discusses the phenomenon of people abandoning HIV-AIDS treatment in three health centres in Mozambique. It results from researches carried out in urban and rural contexts, related to a doctorate degree on “Language, Culture and Society” at the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanity at the Zambeze University, in Mozambique.

In 2021, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has estimated that 45 million people are starving in the region. Draught, floods, and the Covid-19 pandemic are some of the causes of the tragedy. Furthermore, there is lack of food caused by climate changes. The Global Report on Food Crises 20205 reveals that many Mozambican people, particularly under-5 children, present with acute malnutrition. The tropical cyclones Idai and Kenneth have destroyed vast agricultural areas, affecting family incomes. Moreover, the same report states that the floods and draughts in different geographical areas have further exacerbated malnutrition. The environment factor constitutes the core reason why the agriculture production in Mozambique is not coping with the basic food needs of the population.

Some years ago, the main problem was of lack of nutritional educational. As Germano et al. (2007, p.21) argued “often in Africa food that is both abundant and cheap is not used in people’s diet although it may be highly nutritious. People ignore it because they fail to realize their importance”. Today, although this situation is still present in some areas, the problem seems to be a different one. There have been significant changes in nutritional concepts, especially among women who participated, when visiting health centres, in cooking sessions to learn good practices by using cheaper and local products. These sessions continue to take place in different health centres. However, today, especially in Mangunde health centre, one may hardly deliver such sessions to patients who have no food at all. The response to this problem must be approached differently, i.e. providing food to rural communities strongly affected by climate changes.

Methods

Population

This descriptive study, based on interviews, has been conducted from June to August 2021. Overall, the study involved 82 individuals on HIV-AIDS treatment, as well as 70 people sampled from the health staff (including trained volunteers). Patients involved in the study were those who restarted treatment after they had abandoned it. These people had been previously selected by the health centre authorities through an existing list of patients with a history of abandonment. Moreover, this paper focuses also on hunger and nomadism as possible social determinants of HIV/AIDS treatment abandonment. Treatment abandonment, defined as the failure to start or complete a programme of a potentially curative therapy, is a frequent but preventable cause of treatment failure among children, as well as adults.6

Brief evolution of Antiretroviral Treatment in Mozambique

The Mozambican government is dealing with treatment of HIV since 2003, when the Community of Sant´Egidio, introduced the DREAM (Drug Resource Enhancement against AIDS and Malnutrition) programme in Maputo. At that time, many organizations considered inappropriate to introduce treatment. The focus was only prevention by means of condoms. As affirmed by Palombi et al., “In the history of the medicine, no epidemy has been quelled exclusively through prevention. The exclusion of the Africans in the treatment is simply due to lack of will […] moreover, the inefficiency of the drugs due to malnutrition and polluted water may be overcome altogether with domiciliary treatment if also food support and drinking water are guaranteed”, (Palombi, 2008:45).7 In countries like Mozambique, inefficient health systems, delayed diagnosis, lack of physicians and nurses, inadequate supportive care infrastructure, limited access to effective treatment, high rates of treatment-related mortality, increased relapse, and treatment abandonment are common reasons for poor survival rates.8 The treatment of HIV introduced by the Community of Sant’Egidio in Mozambique is free of charge, so to allow everyone getting treated and not abandoning it due to lack of money. As it has been maintained, “A free of charge treatment is beforehand a matter of justice, but the aim is also to support patients to follow the therapy without interrupting it. In fact, the few lucky people in Africa (the ones with money to start the therapy) often interrupt it because they get into economic difficulties with enormous prejudice to the therapy response and ensuing resistance to successive therapies. For DREAM, gratuity and inclusion of those who present with clinical criteria to be included in the programme is a matter of justice, but also backbone to guarantee adherence to therapy” (DREAM, 2008:71).9

But why African governments and the international community hesitated to introduce antiretroviral treatment in Mozambique? According to Germano et al (2007:13) “Failure to adhere to therapy has long been one of the main obstacles to introducing anti-retroviral therapy in resource-limited countries”. While the international wavering continued, rich people were treated and poor people were dying without even being tested.

Before the introduction of antiretroviral treatment, there was a need of convincing the international community and agencies about the approach to be considered for developing countries. It was clear that rich countries could better afford the treatment than poor ones, however, something had to be done to save African lives. According to Marazzi (2009:7),10 “In fact, an AIDS patient has an individual complexity, is not a photocopy of patients who live in rich countries, must be known, studied and we must answer to his or her specific needs in preventive, therapeutics and social terms…” This assumption fostered the ongoing of the DREAM program for Africa, confident that treating AIDS in Africa would not simply mean the provision of drugs, but also nutritional support and other kinds of assistance. Before introducing antiretrovirals in Mozambique, patients infected by HIV used to go to South Africa or other countries, but this was possible only for rich people. Thus, the majority of the infected poor people were receiving a sort of death sentence. “Rurality and poverty often coincide. The rural environment is often characterized by cultural and existential isolation, hard life conditions, lack of transport means, lack of communication, schools, and sanitation. All these often generate a one sense response: flee from countryside and a disordered and rapid urbanization which creates impossible megapoles”, Alumando, (2009:57). From 2003 to 2021 the government has greatly expanded antiretroviral treatment. According to a MISAU report from 2020, out of 1,633 health facilities with ARV treatment, 38 are closed (35 in Cabo Delgado and 3 in Sofala provinces), (MISAU, 2020:54). According to the same MISAU report, the number of people living with HIV and in ARV treatment has increased: “up to the end of December 2020, a total of 1,402,902 patients are reported in active treatment, compared to 1,338,100 active patients at the end of 2019”, (MISAU, 2020:48). The national treatment coverage is 68%. However, in the Sofala province, only 55% of the infected people are on treatment. That is, about half of the infected people are still not being treated.

Adherence and treatment abandonment

Antiretroviral treatment is for the moment a treatment for life. Its interruption causes complications and is usually fatal. A monitoring carried out in 595 health facilities shows that 72-85% of the patients who started ARV treatment continue the treatment after 30 days, on one hand, and from 79-90% of the patients continue the treatment after a period of three months. Summing up, the average of adherence after one and three months is 82% and 85%, respectively (MISAU, 2020:52). What keeps adherence to treatment is not just the availability of the drugs or the infrastructures. More importantly, as Germano et al state, “confidentiality, respect, courtesy, availability of staff, and a pleasant, welcoming environment… are all factors that contribute to patients’ decision to return to the centres for successive treatments” (Germano et al, 2007:13). These factors are important for both the comfort of the patients and the psychological aptitude for adherence.

The causes of abandonment may vary according to the specific country and within the same country, particularly when it undergoes economic and demographic transitions.11 “The follow up of the adherence is crucial to avoid absences and abandons, as well as to reinforce adherence, assuring the improvement of the quality of life of the patients in ARV treatment. It is necessary that the monthly calendar is fulfilled in the first three months from the beginning of the ARV treatment, followed by a trimestral follow up.”, (MISAU, 2020:66).12 That is why patients’ visits are scheduled appropriately. There are trained volunteers who assure the follow-up of the patients, calling by phone those who miss to come to an appointment at the health centre. However, the number of patients who don’t show up or abandon continues to rise. “Adherence to treatment is one of the most critical aspects of a public health approach to HIV control in Africa. In the experience of DREAM, a high level of adherence arises from two factors: assurance of access to treatment; and free of charge treatment.” (Marazzi et all, 2005:19).

Descriptive Outcomes

A 50-year-old patient at Mangunde health centre said: “In the countryside there is no job. The unique job is to go to Machamba (agriculture) to work for others and get paid. Often, we go outside Mangunde to find this job and this is what happened to me. I was out and didn’t manage to come and take drugs for three months”. Such stories are very common for both men and women in Mangunde. The patients are conscious of the importance of the treatment, but their daily struggle for surviving or get stuff to eat doesn’t make them stable. As Bernard Tondé (2016:328) says “AIDS is also a rural problem, not because it ruins sustainable development efforts but also because it threatens food security, hitting agriculture by disseminating the workforce”. For such reasons, an integrated approach in treating HIV patients becomes important for the success of the treatment, especially in rural areas like Mangunde. The patient on treatment and with lack of food will not only interrupt the treatment, but will also, as a consequence of the disease, fail to continue to work. Another patient in the Mangunde health centre said: “Our biggest problem is scarcity of rain and, consequently, we have worse harvestings, and consequently no food. It is complicated to take drugs without having eaten something, and it happened to me”.

A 40-year-old woman in Mangunde said: “I had to abandon the treatment because when taking drugs with empty stomach I couldn’t stand, but when I got something to eat and the activists visited me, I decided to restart the treatment and now I am better nourished”.

A 49-year-old woman in Mangunde, a peasant with six children who has been on treatment for eight years, abandoned in 2019 the treatment: “I had no food and decided by myself to stop taking drugs because I did not feel well after taking drugs without eating something. I became sick and when the situation got worse, I decided to continue treatment, but it is still very difficult because there is no food”.

Laurent Magesa in Azetsop,13 (2016:17) “In many areas of sub-Saharan Africa, however, these medications are still beyond easy reach of the majority of the poor, especially in the rural areas”. Magesa continues arguing that “… poverty is indeed generally acknowledged as a major contributing factor to the spread of the infection”. Also because, citing Eileen Stillwaggon who argues that “HIV transmission is a predictable outcome of an environment of poverty, worsening nutrition, chronic parasitic infection, and limited access to medical care” are all related to poverty. In the same line, Stillwaggon believes that “HIV is a disease of poverty in the African context”.

The reluctance of some governments to fully implement ARV treatment and a food integrated approach to support poor people in treatment justifies treatment abandonment in some patients.

A 32-year-old patient in Mangunde said: “I had to leave Mangunde to Beira looking for better living conditions, and there I didn’t continue taking drugs and became sick”.

A 44-year-old man with five children in Beira, and in treatment at Ponta-gea health centre for two years said: “I am a driver and I often travel abroad, and once I went to Congo for work. I stayed there for more than two months and I had no drugs during that period, but when I came back I went to the health centre but they considered me as an abandon”.

A 56-year-old patient at DREAM centre in Beira, in treatment for 16 years and who has four children, said: “I am a sailor and as you know this work demands going to the sea for a long period and often I don’t come to the health centre for long, but when back home I always come to take the medicine”.

Another patient at Ponta-gea health centre, sixteen years in treatment, said: “I went to Cabo Delgado for work and due to the war I stayed there for six months and I was not taking the drugs during this period. I became sick and came to Beira, but when I arrived at the health centre they had considered me as an abandon”.

Mobility of people from urban to suburb areas were considered in the past to have increased the spread of the virus. Now human mobility, of HIV patients in particular, is becoming one of the reasons of treatment abandonment.

A 48-year-old man in treatment at a DREAM centre, who has three children and has been in treatment for three years said: “I am biscateiro (part-time worker), and we move from one side to another looking for a job, and I went to Inhaminga (200 kilometres from Beira city) and stayed there for a long time. But got sick because I was not taking drugs. Then I couldn’t manage to work and had to come back to Beira. Now I am reintegrated, I am taking drugs and I am feeling well”.

The above declarations demonstrate how hunger and nomadism influence the abandoning of the treatment. There is of course a patient’s responsibility in adherence to treatment, however, there are structural situations which will need a wider intervention. Cahill, edited by Azetsop, (2016:394) wrote “In Africa, the battle against AIDS must be fought on three fronts: taking individual responsibility; changing cultural attitudes and established practices; reducing local, continental, and global structures that cause structural and other forms of injustice”.

Leonardo Palombi (2017) in an article about HIV in Malawi concludes that “Educated, urbanized HIV-infected adults living far from programme centres are at high risk of LTFU, particularly if there is no maternal figure in the household”. Moreover, the same study found out that also distance from the health centres and costs of transportation were factors associated to the abandonment. In Mangunde health centre, some patients reported that they must walk the whole day to reach the health centre where they receive medications. This effort needs energy to walk, in an area where there are no means of transport. This is a problem that must be integrated in designing retention strategies in Africa. In developing countries, as Palombi states, reaching health-care centres is often difficult, and it becomes even more challenging for patients who do not have the resources or energy to seek care. HIV treatment should consider social, economic, and structural contexts to integrate it as part of a holistic approach. “Nevertheless, the correct and effective treatment of HIV requires a comprehensive and multi-dimensional approach and cannot be achieved by merely distributing drugs to patients who qualify for treatment. Diagnostics, strategies that assure adherence to treatment, trained personnel, mechanism for monitoring opportunistic infections and conditions that manifest or co-exist with HIV infections, including malaria, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases and malnutrition, are also required” (Marazzi et al, 2005:2). Considering only drugs as an isolated solution for treating HIV in developing countries will fail. According to UNAIDS, cited by Joseph Healey (2016:80), “to close the gap around access to HIV services will not be met unless the delivery of antiretroviral treatment is radically reshaped into community-led approaches that adapt to the realities of those living with HIV”. In Mangunde and Beira health centres, with the only exception of the DREAM centres, nutritional support to HIV patients is not implemented, and this is justified with the international crises that affect the country.

Results

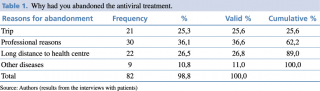

Out of the 82 patients interviewed in the study, professional reasons are the most mentioned determinants (36,6%), followed by the distance from the health centre (26,8%). Also, the trip is mentioned by 25.6% of the respondents, followed by other diseases (11.0%). It is important to clarify that the two determinants, trip and professional reasons, may be considered under the same category (nomadism) as they both describe movements of patients from the usual place of living to another place to look for job, land to cultivate, or other motivations. Long distance to the health centre comes out as a major concern too. In a resource limited setting, like in Mangunde, there are no means of transport and there are patients who have to walk more than 100 kilometres to get to the health centre to receive the drugs (Table 1).

Table 1. Why had you abandoned the antiviral treatment?

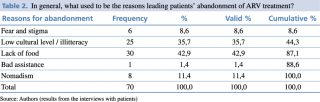

In Table 2, the results of the interviews of the health professionals show a different scenario. Lack of food or hunger have been identified and described as key problems (42,9%) for abandonment, followed by low cultural level/illiteracy and nomadism. In the experience of professionals, stigma and bad quality of care do not appear significant reasons.

Table 2. In general, what used to be the reasons leading patients’ abandonment of ARV treatment?

Discussion

Many studies investigated the LTFU (Loss to Follow Up) phenomenon, especially at clinical and biomedical level. However, different researchers were not in agreement about possible subjective or objective perspectives on the reasons (social, cultural, or economic) that led patients to abandonment.

The present study did not show evidence of cultural determinants associated with abandonment. Interestingly, patients report that long distances to the health centres is an important determinant of abandonment, representing 26.8% of the responses. Among health professionals this determinant is marginal (1.4%). Nomadism has never been considered by professionals as a reason for abandoning treatment, even if more than 60% of the patients consider it as a key reason. Such a perception mismatch between patients and professionals is highlighted by the fact that a meaningful number of professionals (21.4%) does not know why their patients abandon treatment. However, it should be mentioned that more than 70% of the interviewed professionals were trained volunteers, rather than nurses or doctors.

Of course, there are problems and conditions that are difficult to be reported in an interview, such as poverty, hunger, or stigma. In any case, the strong relationship between patients and peer educators or trained volunteers allowed the authors to explore hidden reasons or knowledge in these fields, namely lack of food and low cultural level/illiteracy. In fact, the trained volunteers who work daily with the patients, visiting them at homes and encouraging them to continue the treatment, develop a better understanding of the difficulties the patients are facing in continuing the treatment.

Summing up, hunger, illiteracy and nomadism are key problems, all directly related to poverty. Therefore, different variables associated with poverty determine the abandonment of most of the interviewed patients. Lack of money to get a transport to the health centre, lack of money to buy food and moving from one place to another (nomadism) looking for better living conditions are actually all poverty variables. The intervention of trained volunteers plays an important role for the reintegration of the patients who had abandoned treatment.

Conclusion

Among the different social, cultural, and economic reasons leading to HIV treatment abandonment, hunger, illiteracy and nomadism were reported by the studied population.

Mozambique, a country with limited resources, in order to overcome the abandonment phenomenon will have to adopt a holistic approach in HIV/AIDS treatment strategies. Peer educators and trained volunteers seem to be a key element in supporting patients throughout a long lifelong treatment. This may improve the compliance of the patients and, consequently, improve the control of the HIV/AIDS epidemics. High level of poverty in the country, including bad heath conditions, lack of specialized health staff, or lack of roads and means of transportation are widely seen as factors affecting the HIV/AIDS treatment policies. We are convinced that human resources, one richness of the country, could be the best answer to solve at least part of the problems of compliance.

Treatment should be considered in a proper context. Social, economic, cultural, and anthropological features of the population must be considered to promote and implement an effective health system that can benefit all. The role of trained volunteers and peer educators must be supported, so to improve adherence of the patients.

Acknowledgment

We thank the DREAM Program staff for making data available and for its efforts in fighting HIV/AIDS.

References

- World Population Review: HIV Rates by Country, 2021. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hiv-rates-by-country.

- P Tezera Moshago Berheto, Demissew Berihun Haile, Salahuddin Mohammed: Predictors of Loss to follow-up in Patients Living with HIV/AIDS after Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy. N Am J Med Sci. 2014 Sep;6(9):453-9. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.141636.

- S. Mpinganjira, T. Tchereni, A. Gunda, and V. Mwapasa: Factors Associated with Loss-to-Follow-up of HIV-Positive Mothers and Their Infants Enrolled in HIV Care Clinic: A Qualitative Study. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20:298.

- Kebede Embaye Gezae, Haftom Temesgen Abebe & Letekirstos Gebreegziabher Gebretsadik: Incidence and Predictors of LTFU among Adults with TB/HIV Co-infection in Two Governmental Hospitals, Mekelle, Ethiopia, 2009–2016: Survival Model Approach. BMC Infect Dis 19, 107 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3756-2

- Global Report on Food Crises 2020

- Weaver MS, Arora RS, Howard SC, et al A Practical Approach to Reporting Treatment Abandonment in Pediatric Chronic Conditions. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2015;62:565–70.doi:10.1002/pbc.25403

- Palombi, L. (2017). Who Will Be Lost? Identifying Patients at Risk of Loss-to Follow-up in Malawi. The DREAM Program Experience.

- Pui CH, Yang JJ, Bhakta N, et al Global Efforts Toward the Cure of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018; 2:440–54. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30066-X

- DREAM, Comunidade de Sant´Egidio, 2008. Viva a Africa Viva! Derrotar a SIDA e a Malnutrição, Leonardo International, Roma.

- Marazzi, M.C. (2017). DREAM: An Integrated Faith-Based Initiative Treat HIV/AIDS in Mozambique, Case Study.

- Wang YR, Jin RM, Xu JW, et al Treatment Refusal and Abandonment in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011; 28:249–50. doi:10.3109/08880018.2010.537436

- MISAU (2020). Relatório Anual sobre HIV/SIDA.

- Azetsop, J. (2016). HIV & AIDS in Africa. Christian Reflection, Public Health, Social Transformation, Orbis Books, USA.